The soles of Ruben’s feet are made of rubber balls. His laughter is like a lawnmower engine. He flips crude jokes about your mother like pancakes on a Sunday. High energy barely describes this high school freshman: he took two PE classes in back-to-back class periods and still snuck out of math to play handball with someone, anyone, or even all alone.

Helping Ruben write an essay seemed like an exercise in futility since it was hard to imagine containing his joie de vivre. In actuality, the real difficulty rested in his limited language ability.

Six months ago Ruben came to the United States, after crossing three borders. He came on his own to join his family and to seek amnesty. He briefly attended school as a child, but had huge lapses in his education–the most recent of which occurred before entering American schools. In Los Angeles, where he lives and where UCLA Writing Project fellows work with teachers and students, he was assigned a school due to his age (seventeen) and not his reading level (pre-Kindergarten).

Ruben burns himself into teachers’ memories, but his story is common in South Los Angeles: we have seen wave after wave of students who are learning English as an additional language for the first time in high school. Most are extremely motivated to take every educational opportunity they are offered. The vast majority that arrive in South LA are escaping violence, poverty, and are looking for a better life with few-to-no traditional resources at their disposal.

The first day of school, students come to class dressed in uniform, pencils ready, and sit apprehensively in English Language Development 1A. They aren’t registered (what does that even mean? they wonder) and the thoughtful, kind teacher who has shepherded my school’s ELD 1A students for the last decade walks them to the registration office and then back to her room.

They are safe now. They can begin learning to read and write or, for some, begin learning the alphabet for the first time. She teaches them.

This teacher is excluded from English professional development (but her students can’t read, say the administrators) and often doesn’t have a grade-level team to join (some of her “freshmen” are twenty years old and have very different needs from the average fourteen-year-old). In some schools, she is replaced by computer programs like Rosetta Stone. She, and colleagues that own the six semesters of early and intermediate language development on campus, teach the most at-risk students in the school in almost total isolation. They learned this was common for ELD teachers across the county and state.

What does College, Career, and Community Writers Program (C3WP) look like for these students, our students, for Ruben?

When we strip away the scripted curriculums and imagine life for a target group of students with a 65-75% drop out rate, what does it mean to engage these students in meaningful literacy and writing practices? To prepare them for life after high school and, hopefully one day, as they continue their education?

Everything is at stake here, since these students are living in one of the poorest communities west of the Mississippi and are required to become functionally literate within two years in order to begin “regular” English classes and graduate on time. This is an extreme example, but English Learners are often on the margins in schools across the country; extraordinary teachers everywhere are working to improve their lives and their schooling experience. How can we help teachers of English learners engage students in writing?

Leaders at the UCLA Writing Project, with a grant from the National Writing Project, designed a plan to engage English learners and their teachers with C3WP. Building on Jean Anyon’s research on class and schooling, we imagined what outcomes would be if we knew all students should engage in routine argument writing and critical reading. We studied models of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy from Alim and Paris and centered discussions on the legitimate needs of students.

Source materials and classroom experiences were designed to acknowledge the trauma many students face traveling across countries on their own as they flee violence; they needed to read research and stories about their experiences and tell their stories; we did not, could not, throw out narratives. As a team, we backwards-planned what students would be able to do at each level of language development, always with the end goal that students who begin to mainstream into regular English would be prepared to complete source-based writing as well as their fluent peers.

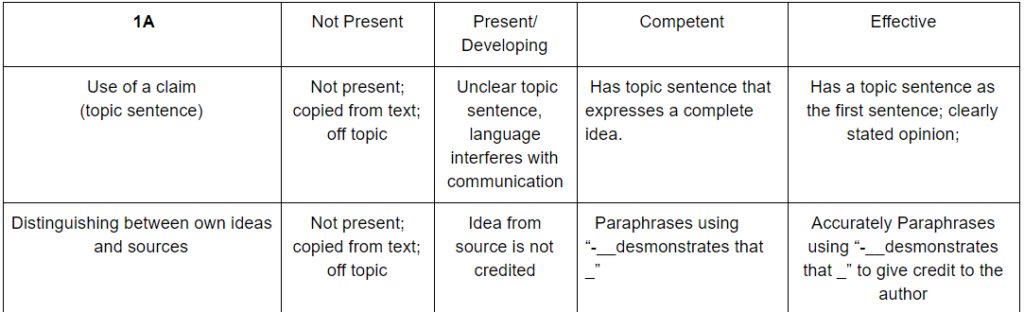

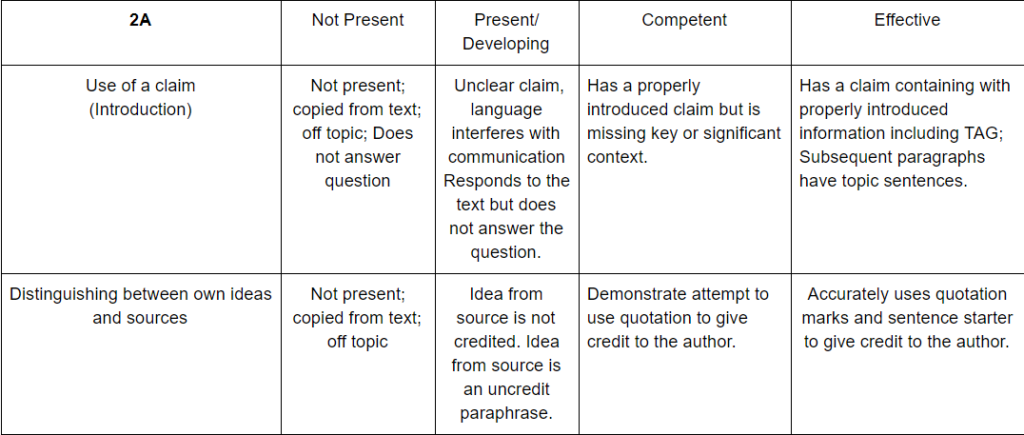

This is the hefty goal of the Using Sources Tool, one of C3WP’s formative assessments, and one that we hope will prepare students to engage critically with the world around them. An example of levels of progression might include:

Image credit: Mayra Rodriguez, C3WP participant

With a goal in mind, students create portfolios each semester to track their growth and to show improvements in writing over time. These victories help students (and teachers) engage and maintain hope. Portfolios of work also expose gaps in curriculum and skills and help teachers understand how to adjust curricula to scaffold reading for a purpose and writing with style.

Expectations are rigorous but also realistic. Teachers adapt texts, using sites like Newsela.com and even their own children’s picture books, to ensure students are able to practice the skills of source-based writing at every level of English acquisition. Among discussions of writing, teachers also realize they need to adjust placements and offer more students individualized attention. C3WP is everyone’s first experience with professional development that focuses purely on the students’ needs to support their learning.

In this last year, students wrote. Even Ruben wrote. Teachers passed his essays in circles, with sighs of relief and joy. The focus on writing rippled outward to every student, even those with high needs. The time to confer around papers became the most valuable professional development. It became proof that English learners at every level can write, should write.

Ruben dropped out of school in early January. It was his fifth semester and, like that vast majority of his peers, he needed to begin working to support himself and his family. He might attend night school, one day.

For now, he is a day laborer. He, like so many of his peers, is invisible. They attend high school and learn some conversational English before entering the workforce and ending their education. They have few alternatives. We hope we helped them become a bit more community and career ready, as well as, one day, college ready, and each day matters as if it will be the last. We work to change expectations for these young people and give them more social and community supports (that is a different blog entry for a different day), but we also sprint to engage them in meaningful literacy each day that we have the opportunity to have them in our classes.

By Kate Rowley